Lightfield Cameras

This project explores light field camera techniques by manipulating a grid of images taken along a single axis, demonstrating how shifting and averaging multiple images can simulate complex camera effects like depth refocusing and aperture adjustment. By capturing light rays from different perspectives, the project allows computational reconstruction of focus and aperture characteristics, revealing how simple mathematical operations can create sophisticated visual transformations that mimic advanced camera capabilities.

Depth Refocusing

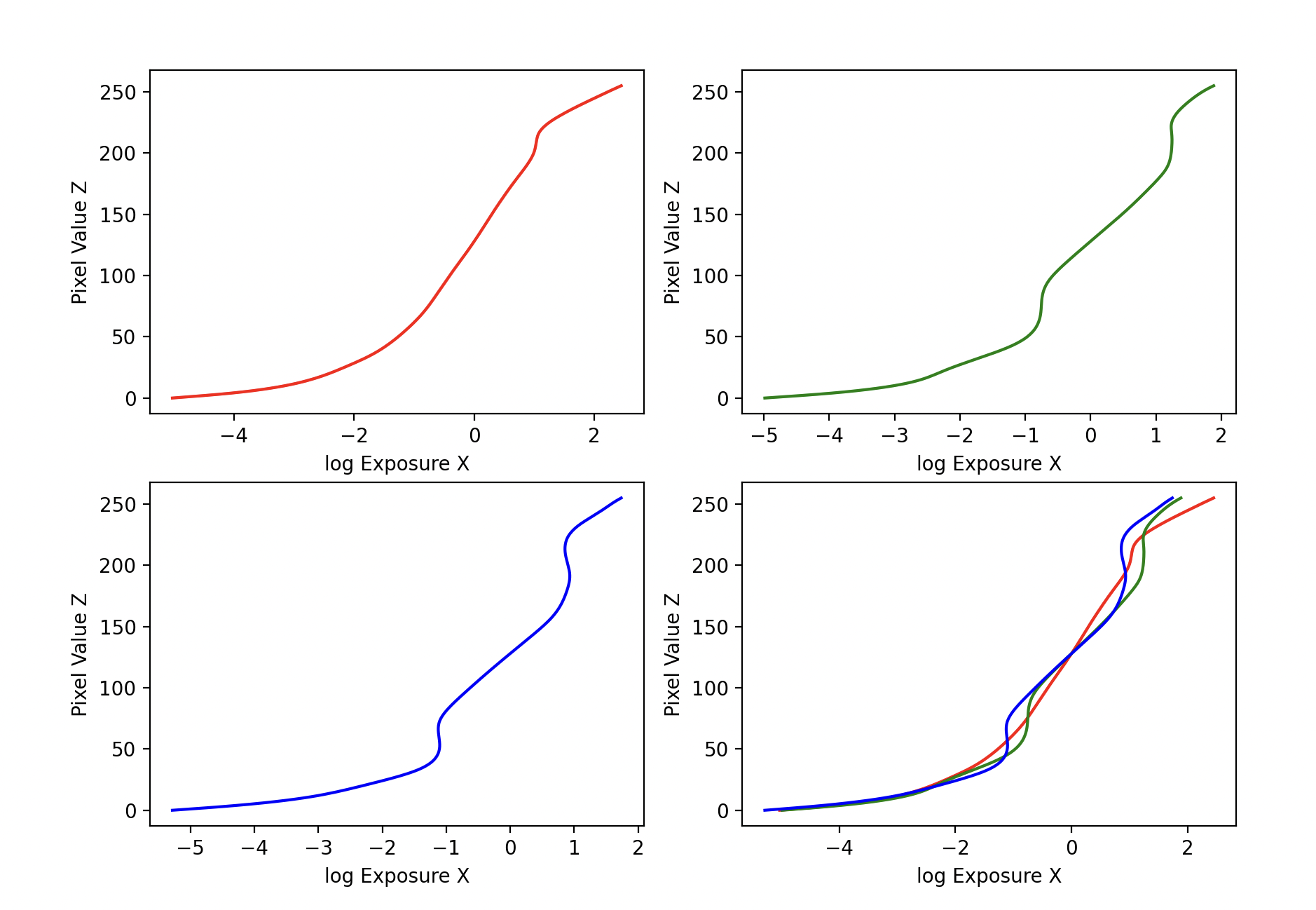

Depth refocusing is a computational photography technique that exploits the parallax effect, where light rays from different points in a scene arrive at slightly different angles when the camera moves. By capturing a grid of images along a single axis, the technique captures how light rays from objects at different distances shift relative to each other, creating a unique depth-dependent positioning effect. The method centers on a reference image and shifts surrounding images using a scaling factor (alpha), which mathematically adjusts the trajectories of these light rays to simulate different focal planes. As nearby objects cause more significant light ray displacement compared to distant objects, the shifting and averaging process creates images that can selectively sharpen or blur different depth regions. By using alpha values ranging from -1 to 3, the technique manipulates these light ray intersections, effectively allowing computational reconstruction of focus at various depths without physically changing the camera's lens.

Depth Refocusing Gif (CLICK TO RESTART GIF)

Aperture Adjustment

Aperture adjustment is a computational photography technique that simulates different camera aperture sizes by strategically selecting and averaging images from a light field grid. The implementation uses a radius-based approach to gradually reduce the number of images used in averaging, effectively mimicking how a smaller aperture would narrow the light gathering area of a camera. By selecting images from a central region of the grid and progressively reducing this region (from a radius of 0 to 7), the method creates a series of images that demonstrate how the apparent aperture size affects image sharpness and light gathering, without physically changing a camera lens. The code iterates through different radii, averaging only the images within that radius around a central reference point, which creates a computational representation of aperture adjustment that showcases how fewer light rays contribute to the final image. This technique allows for exploring depth of field and light gathering characteristics through simple mathematical operations on a grid of images taken from slightly different perspectives.

Depth Refocusing Gif (CLICK TO RESTART GIF)

Summary

In this project, I learned that light field photography allows me to computationally manipulate images captured from multiple perspectives to simulate advanced camera techniques like depth refocusing and aperture adjustment without physically changing lens properties. By understanding how light rays from different scene depths shift across a grid of images, I discovered that simple mathematical operations like shifting and averaging can dramatically transform image characteristics, effectively reconstructing focus and depth information. I learned that the parallax effect—where nearby objects move more significantly across images compared to distant objects—can be leveraged to create computational photography effects that mimic complex optical systems. The project showed me that a grid of images captures not just a single moment, but a rich, multidimensional representation of light rays passing through different points in space, allowing for post-capture manipulation of visual properties. Most importantly, I gained insight into how computational techniques can deconstruct and reconstruct visual information by treating images as data to be mathematically transformed, revealing the underlying computational principles that make advanced imaging techniques possible.

Bells and Whistles: Using Real Data

In this part, I took my own pictures to simulate a light field camera. I drew a 5x5 grid on my desk, drawing spaces 2.5 inches apart. My results for depth refocusing and aperture adjustment were quite blurry. I imagine this is due to the lack of precision in exact grid positions and angles for the effects to be successful. I also only had a 5x5 grid, which may not be large enough.

Depth Refocusing (CLICK TO RESTART GIF)

Aperture Adjustment (CLICK TO RESTART GIF)